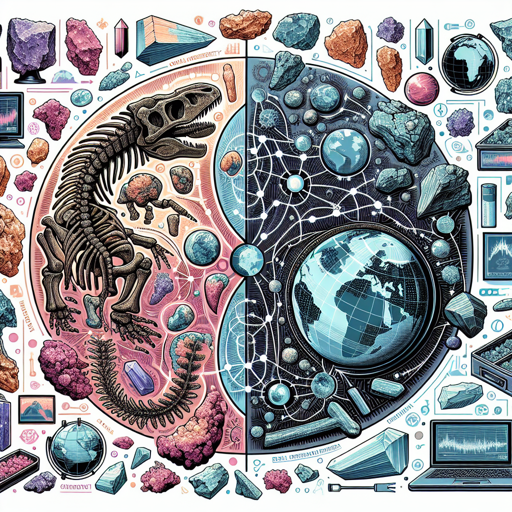

Fossils vs Minerals Understanding Core Differences

Discover how fossils and minerals differ in origin, nature, and significance in geology.

Introduction

Step into any natural history museum or browse a geology collection, and you’ll encounter two of the most captivating relics of Earth’s past: fossils and minerals. Both are prized by collectors, studied by scientists, and admired by enthusiasts worldwide. Yet, they often sit side by side in displays, leading to confusion among new enthusiasts and students alike. What truly separates a fossil from a mineral specimen? Why do their stories matter to geology and earth science?

Whether you’re a seasoned rockhound, an educator guiding the next generation, or simply curious about the wonders beneath our feet, understanding the distinction between fossils and minerals is fundamental. In this article, we’ll clarify their differences, explore their origins, and illuminate their roles in unraveling the mysteries of our planet.

Fossils and Minerals: Defining the Basics

What is a Mineral?

Minerals are naturally occurring, inorganic solids with a definite chemical composition and an ordered atomic structure. With over 5,000 known species, minerals form the backbone of Earth’s crust and are responsible for much of its color, texture, and structure. Classic examples include quartz (SiO₂), calcite (CaCO₃), and pyrite (FeS₂).

What is a Fossil?

A fossil is any preserved evidence of ancient life—be it plant, animal, or even microbial. Fossils include bones, shells, leaves, footprints, burrows, and even traces of ancient DNA. Unlike minerals, fossils begin as organic materials that undergo various processes (like permineralization or carbonization) and are preserved within sedimentary rocks.

“Fossils are not only windows into the past—they are keys to understanding our place in Earth’s history.”

— Dr. Jane Goodall

Key Differences at a Glance

The following table summarizes the essential differences between fossils and minerals:

| Feature | Minerals | Fossils |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Inorganic crystalline solids | Preserved remains or traces of ancient life |

| Origin | Formed by geological processes | Result from biological activity + preservation |

| Composition | Definite chemical formula | Organic material replaced/encased by minerals |

| Structure | Ordered atomic pattern (crystals) | Variable; often lack crystalline structure |

| Examples | Quartz, calcite, pyrite, feldspar | Dinosaur bones, ammonite shells, petrified wood |

| Formation Environment | Igneous, metamorphic, sedimentary rocks | Mostly sedimentary rocks |

| Scientific Significance | Geochemistry, resource extraction | Paleontology, evolutionary history |

How Are Minerals Formed?

Minerals can crystallize from molten rock (magma or lava), precipitate from saturated solutions (as in caves or hot springs), or undergo transformation during metamorphism. Their formation is driven by changes in temperature, pressure, and chemical environments. For example:

- Quartz forms as magma cools or as silica-rich water evaporates.

- Calcite can precipitate from marine waters to form limestone or crystallize in caves as stalactites.

- Pyrite, known as “fool’s gold,” forms in hydrothermal veins or sedimentary rocks under low-oxygen conditions.

Each mineral’s distinct crystal shape (“habit”), hardness (as measured on Mohs scale), color, luster, and other physical properties aid their identification.

How Do Fossils Form?

Fossilization is a rare event requiring specific conditions. The main steps include:

- Death and Burial: An organism dies and is rapidly buried by sediment (mud, sand, volcanic ash), protecting it from scavengers and decay.

- Preservation: Over time, organic material may decay while hard parts (bones, shells) remain. Minerals may seep in and replace these parts—this process is called permineralization.

- Exposure: Geological forces may later expose the fossilized remains at the surface.

There are several types of fossils:

- Body Fossils: Actual remains such as bones, teeth, shells.

- Trace Fossils: Imprints or evidence of activity—footprints, burrows.

- Molecular Fossils: Organic molecules or DNA remnants.

Common fossilization processes:

- Permineralization: Minerals fill cellular spaces and crystallize.

- Carbonization: Organic material leaves a thin carbon film.

- Molds and Casts: Organism leaves an impression; minerals fill the void.

Composition: The Mineral-Fossil Connection

While minerals are always inorganic by definition, many fossils owe their preservation to mineral processes. For example:

- The bone of a dinosaur may be replaced molecule by molecule with silica (forming a quartz fossil) or calcite.

- Petrified wood occurs when wood fibers are replaced with minerals like chalcedony.

This overlap sometimes leads to confusion—fossils can be “made” of minerals! But what matters is the origin: fossils began as living organisms; minerals never did.

Scientific Significance

Why Study Minerals?

Minerals reveal clues about Earth’s formation and ongoing processes. Their distribution tells us about mountain-building events, volcanic eruptions, and even clues to ore deposits essential for technology (like lithium for batteries).

Geologists use minerals to:

- Date rocks using isotopic methods.

- Reconstruct past environments (e.g., evaporite minerals signal ancient seas).

- Guide resource extraction for metals and industrial materials.

Why Study Fossils?

Fossils are windows into the history of life. They:

- Chart evolutionary changes over millions of years.

- Reveal ancient climates (paleoclimate) and environments (paleoecology).

- Help correlate rock layers across continents (biostratigraphy).

Without fossils, we would know little about extinct creatures or how life responded to mass extinctions and changing climates.

Common Misconceptions

-

“All shiny rocks are minerals.”

Not necessarily! Some fossils (like opalized shells) can shine just as brilliantly. -

“Fossils are always bones.”

Many fossils are leaves, shells, eggshells—or even tiny pollen grains! -

“Fossils form only in stone.”

Most do—but some fossils are preserved in amber or ice. -

“Minerals must be beautiful crystals.”

Many are dull clays or opaque masses invisible to the naked eye.

Identifying Specimens: Fossil or Mineral?

Here are some practical tips for distinguishing between the two:

Ask Yourself:

- Does the specimen show symmetry or crystal faces? (Likely a mineral.)

- Are there patterns resembling shells, bone structures, or plant material? (Likely a fossil.)

- Is there evidence of organic shapes—branching veins or cellular textures?

- Try a streak test on unglazed porcelain—a true mineral will often leave a characteristic streak color.

- Use a hand lens: fossils may show tiny growth rings or pores; minerals will show crystal structure.

When in Doubt:

Consult with local geology societies or museums—experts can often identify specimens based on context and appearance.

The Intersection: When Fossils Become Minerals

Some of the most prized fossils are also dazzling mineral specimens. Petrified wood from Arizona’s Painted Desert gleams with agate or jasper hues; ammonites from Madagascar may be opalized with rainbow colors. These “mineralized fossils” bridge both worlds—biological history encased in geological beauty.

Table: Fossilization Processes vs Mineral Formation

| Process | Fossilization Example | Mineral Formation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Replacement | Silicified dinosaur bone | Quartz crystal growth |

| Permineralization | Petrified wood | Calcite stalactites |

| Carbonization | Plant imprints in shale | Graphite veins |

| Molding/Casting | Ammonite molds in limestone | Geode formation |

| Precipitation | Shells encased in pyrite | Halite crystals from seawater |

Educational Use: Bringing It Into the Classroom

For educators teaching geology, minerals and fossils offer hands-on opportunities for engagement:

- Field Trips: Visit local quarries or fossil beds to collect specimens.

- Classroom Labs: Examine samples under microscopes; compare physical properties.

- Cross-disciplinary Links: Connect biology (evolution) with earth science (rock cycle).

Encourage students to keep field notebooks and sketch their observations—a practice used by professional geologists and paleontologists alike!

Further Exploration

For those eager to dive deeper:

- Visit curated collections at museums such as the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

- Join local rockhounding groups—often affiliated with universities or geological societies.

- Explore online resources like Mindat.org for mineral data or Paleobiology Database for fossil records.

Conclusion

Fossils and minerals each tell their own story—one about life’s unfolding drama across eons; the other about Earth’s dynamic forces shaping continents and oceans. While they may sometimes share display cases or even intermingle within a single specimen, their origins—and scientific significance—remain distinct.

For geology enthusiasts and students alike, learning to distinguish between them opens up new worlds of discovery. So next time you pick up a stone on a hike or marvel at a museum exhibit, ask yourself: Is this a relic of ancient life? Or a marvel of Earth’s chemistry? In seeking the answer you’ll join generations of explorers who have helped unravel our planet’s secrets—one specimen at a time.

“Nature conceals under one stone many mysteries.”

— Paracelsus

External Reference:

For an in-depth overview on minerals and fossils, visit the Mineralogical Society of America: Mineralogy 4 Kids.