The Science of Crystal Formation Explained

Discover how crystals form and what makes their intricate structures so captivating to scientists and collectors.

Introduction

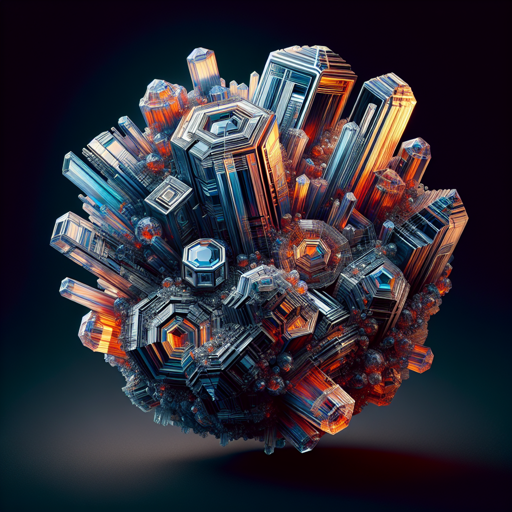

From the delicate sparkle of snowflakes to the grandeur of amethyst geodes, crystals have fascinated humanity for centuries. Their striking geometries, vibrant colors, and intrinsic order seem almost magical—yet, the science of crystal formation is a rich field that bridges chemistry, physics, and geology. For geology enthusiasts, educators, and students alike, understanding how crystals form unlocks deeper insights into Earth’s processes and the hidden beauty within rocks and minerals.

In this article, we’ll journey through the science of crystal formation—exploring how atoms assemble into intricate lattices, why crystals grow into their characteristic shapes, and what these processes reveal about our planet. Whether you’re drawn by the allure of gemstones or the fundamental principles of mineralogy, prepare to uncover the secrets behind nature’s most dazzling structures.

What Is a Crystal? The Building Blocks of Order

At its core, a crystal is a solid material whose atoms or molecules are arranged in an orderly, repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions. This regularity distinguishes crystals from amorphous solids like glass, where atomic arrangement is disordered.

The smallest repeating unit in a crystal is called the unit cell—a tiny box that contains a specific arrangement of atoms. By repeating this unit in space, the crystal builds up its macroscopic shape. The symmetry and dimensions of the unit cell determine the external form and internal properties of the crystal.

Why Are Crystals So Fascinating?

Crystals captivate us for several reasons:

- Symmetry and beauty: Their geometric forms often reflect perfect symmetry.

- Predictable properties: The orderly atomic arrangement imparts unique optical, electrical, and mechanical properties.

- Natural recorders: Crystals can capture information about the geological environments in which they formed.

“Crystals are living geometry—nature’s proof that order can arise from chaos.”

— Dr. Dana Perkins, Geologist

The Science Behind Crystal Formation

Understanding crystal growth requires delving into chemistry, physics, and environmental conditions. Three main stages define the process:

1. Nucleation: The Birth of a Crystal

Crystal formation begins with nucleation—the initial assembly of atoms or molecules into a small cluster that has the potential to grow.

- Homogeneous nucleation: Occurs spontaneously in a uniform environment (e.g., supersaturated solution or cooling magma).

- Heterogeneous nucleation: Initiated on surfaces or impurities, which lower the energy barrier for crystal formation.

For example, when magma cools below a certain temperature or when a solution becomes supersaturated with dissolved minerals, atoms begin to stick together to form stable nuclei.

2. Crystal Growth: Building Complexity

Once a stable nucleus forms, it acts as a seed for further growth. Atoms or molecules continue to attach themselves to the existing structure in a highly ordered fashion.

Factors influencing crystal growth include:

- Temperature: Affects how quickly atoms move and attach.

- Concentration: Higher concentrations of building units promote faster growth.

- Time: Slow cooling or evaporation generally yields larger, better-formed crystals.

The final shape of a crystal is dictated by its internal symmetry (as determined by its unit cell) and environmental conditions during growth.

3. Termination: When Growth Stops

Crystal growth halts when:

- The supply of building units is exhausted,

- Environmental conditions change (e.g., temperature drops below freezing point),

- Or physical space becomes limited.

Crystals that have grown freely often display well-formed faces; those constrained by surrounding material may be irregular or interlocked.

Types of Crystal Systems

Crystals are classified into seven basic crystal systems, defined by their unit cell geometry:

| Crystal System | Unit Cell Axes | Angles Between Axes | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic (Isometric) | a = b = c | α = β = γ = 90° | Pyrite, Halite |

| Tetragonal | a = b ≠ c | α = β = γ = 90° | Zircon |

| Orthorhombic | a ≠ b ≠ c | α = β = γ = 90° | Olivine |

| Hexagonal | a = b ≠ c | α = β = 90°, γ = 120° | Quartz |

| Trigonal | a = b = c | α = β = γ ≠ 90° | Calcite |

| Monoclinic | a ≠ b ≠ c | α = γ = 90°, β ≠ 90° | Gypsum |

| Triclinic | a ≠ b ≠ c | α ≠ β ≠ γ ≠ 90° | Kyanite |

Each system dictates possible external shapes (habits) and internal symmetries, influencing everything from optical behavior to cleavage patterns.

Environments Where Crystals Form

Crystals can grow in a variety of natural environments, each producing unique mineral specimens:

Igneous Environments

When molten rock (magma or lava) cools and solidifies, minerals crystallize out of the melt. Slow cooling inside Earth’s crust allows large crystals to develop (e.g., granite’s feldspar), while rapid cooling at the surface creates fine-grained rocks (e.g., basalt).

Sedimentary Environments

Minerals can precipitate from water to form sedimentary rocks. Evaporation of saline lakes may yield halite (rock salt) or gypsum crystals.

Metamorphic Environments

Under high pressure and temperature within Earth’s crust, existing minerals may recrystallize without melting. This process can create impressive crystals such as garnet within schist.

Hydrothermal Veins

Hot water rich in dissolved minerals moves through cracks in rocks. As it cools or reacts with host rocks, minerals like quartz or gold crystallize out—sometimes forming spectacular veins or pockets.

Why Do Crystals Grow into Different Shapes?

A single mineral species can develop various external shapes (called crystal habits) depending on growth conditions. For example:

- Quartz can appear as prismatic points, massive forms, or drusy coatings.

- Calcite may form scalenohedrons (“dogtooth” spar), rhombohedrons, or even delicate needles.

Key factors affecting habit include:

- Rate of growth: Rapid growth may produce elongated or skeletal forms.

- Space availability: Limited space leads to intergrown or distorted crystals.

- Impurities: Trace elements can change growth rates on different faces.

- Temperature and pressure: Influence which faces grow fastest.

This diversity is why even common minerals can delight collectors with endless variety!

The Role of Impurities and Defects

No natural crystal is truly perfect. Impurities—atoms not part of the ideal composition—can substitute into the crystal structure. These trace elements often produce vivid colors (e.g., chromium gives emerald its green hue), fluorescence, or even change a gemstone’s value.

Defects such as vacancies (missing atoms) or dislocations (misaligned planes) also impact physical properties. In industry, controlled introduction of defects is used to tailor materials for electronics and lasers.

Famous Crystals and Their Stories

Some crystals have achieved legendary status due to their size or beauty:

- The Cullinan Diamond: The largest gem-quality diamond ever found (3,106 carats), discovered in South Africa in 1905.

- Giant Selenite Crystals: In Mexico’s Naica Mine, selenite crystals up to 12 meters long formed due to stable hydrothermal conditions over thousands of years.

- Herkimer “Diamonds”: Doubly terminated quartz crystals from New York State, prized by collectors for their clarity and unique form.

These specimens are not just natural wonders—they are clues to the geological history and chemical environment in which they formed.

Table: Comparing Crystal Formation Environments

| Environment | Formation Process | Typical Minerals | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Igneous | Cooling/solidification of magma | Feldspar, Quartz | Large crystals if slow cooling |

| Sedimentary | Precipitation from solution | Halite, Gypsum | Layered deposits; often transparent |

| Metamorphic | Recrystallization under pressure | Garnet, Staurolite | New minerals from old ones |

| Hydrothermal | Precipitation from hot fluids | Quartz, Gold | Veins; large clear crystals |

| Surface | Evaporation/freezing | Snowflakes | Delicate symmetry; rapid formation |

Crystals: More Than Just Beauty

For geologists and earth scientists, crystals are more than aesthetic marvels—they are records of Earth’s dynamic systems. By studying crystal size, shape, inclusions, and orientation, scientists can deduce:

- Cooling rates of magmas,

- Temperature and pressure conditions,

- Chemical composition of ancient environments,

- Rates of geological processes.

In industry, synthetic crystals like silicon wafers underpin modern electronics. Gemologists use knowledge of crystal structure to authenticate stones and identify treatments.

Resources for Further Exploration

To deepen your understanding of crystal formation and mineralogy:

- Mineralogical Society of America: Crystallization

- Mindat.org — A database with photos and details on thousands of minerals.

- USGS: Minerals Information

Conclusion

Crystals stand as nature’s testament to order amidst seeming chaos—each one a product of precise atomic choreography shaped by Earth’s ever-changing environments. To study crystal formation is to peer into the heart of geology itself: to witness how elements combine under pressure and time to create both everyday rocks and treasures beyond compare.

Whether you’re marveling at museum specimens or examining grains under a microscope, remember: every crystal holds a story written in symmetry and time. As you continue your journey through mineralogy and earth science, let these stories inspire awe—and perhaps spark your own discoveries in nature’s dazzling world of crystals.